Debut Author Interview with Jamilah Thompkins-Bigelow on her Middle Grade novel GROUNDED

I’m so excited to be able to interview the talented author Jamilah Thompkins-Bigelow on her book GROUNDED, co-authored by S.K. Ali, Aisha Saeed, and Huda Al-Marashi, and published by Abrams on May 9th of 2023.

Jamilah’s picture books are absolutely breathtaking, and I am delighted to say that so is her Middle Grade writing! I loved every bit of this spectacular Muslim book!

I encourage every teacher and librarian to stock this wonderful book on their shelves, and I am sure every reader will love reading this book about four Muslim kids stranded at the airport (and their adventures within).

About GROUNDED:

Description taken from the publisher:

Four kids meet at an airport for one unforgettable night in this middle-grade novel by four bestselling and award-winning authors—Aisha Saeed, Huda Al-Marashi, Jamilah Thompkins-Bigelow, and S. K. Ali.

When a thunderstorm grounds all flights following a huge Muslim convention, four unlikely kids are thrown together. Feek is stuck babysitting his younger sister, but he’d rather be writing a poem that’s good enough for his dad, a famous poet and rapper. Hanna is intent on finding a lost cat in the airport—and also on avoiding a conversation with her dad about him possibly remarrying. Sami is struggling with his anxiety and worried that he’ll miss the karate tournament that he’s trained so hard for. And Nora has to deal with the pressure of being the daughter of a prominent congresswoman, when all she really wants to do is make fun NokNok videos. These kids don’t seem to have much in common—yet.

Told in alternating points of view, Grounded tells the story of one unexpected night that will change these kids forever.

Interview with Jamilah Thompkins-Bigelow:

I loved getting to talk to Jamilah about her book and I think you will enjoy meeting her and her character Feek as well!

SSS: What is the inspiration behind Grounded? And how did you and the other lovely authors decide to co-author this book?

JTB: The inspiration initially came from Aisha Saeed. While waiting in an airport, she imagined four unlikely kids meeting and bonding there. She liked the idea of having different Muslim voices in the narrative and invited me, Huda, and S.K. Ali to join on the project. We had all worked together previously on Once Upon an Eid. From there, our ideas for the book came from fun, collaborative conversations. Aisha came up with some broad strokes suggestions about who the characters might be and we each took a character and developed those ideas more fully and added in our own specifics.

SSS: So many important and wonderful themes in your book- and I have heard mention by the other authors on the importance of the inclusion of Muslim joy in particular – could you elaborate on which themes resonate the most for YOU, and what you hope will be the most impactful for young readers.

JTB: One theme that resonated most was the self-acceptance piece. A few of the Grounded characters are struggling with accepting who they are and have to work through that. That theme comes up a lot in many of my other books because I think it’s such a huge thing for young people and even for older people as we make it through life. Another was about the difficulty of voicing our emotional needs. Kids need to learn how to advocate for themselves and I love how we built in moments where that is explicitly talked about amongst the characters.

SSS: The character of Feek is so adorable and I wanted to reach through the pages and hug him! How did you develop his characters?

JTB: Awww, thank you! Feek is a combination of a lot of preteen and teen boys I’ve seen who are trying to put on a tough and cool exterior when really they are softies inside. I’ve worked with a lot of Black boys in my career in that age group (not to mention having two sons), and it’s always struck me how fragile, sensitive, and multifaceted they can be in spite of the ways the world perceives them. I’m also interested in the challenges of performing masculinity as a young boy. I wanted to explore those things with Feek’s character. Additionally, I thought about the spoken word component of many Muslim conferences and was inspired to somehow add that into the book. As I was writing Feek’s character, he often spoke to me in rhyme and made it clear to me he was a lyricist dying to get out.

SSS: Diverse books are so important (and a passion of mine!). How does being both Black and Muslim affect your writing? (BTW we need MORE!)

JTB: I definitely agree we need more. I write my experience. Period. That can be hard when the expectation seems to be to erase either my Muslimness or Blackness in books. But I stick to writing my experience as unapologetically as I can.

SSS: Will there be more Middle Grade books from you in the future? (Please say YES!)

JTB: Yes! Although nothing is ready to be announced.

SSS: ****Excited Squeal***

Link to preorder Grounded here.

Writing Process

SSS: How long did it take to write Grounded? Do you find it a more difficult process to write Picture Books or Middle Grade books?

JTB: It was definitely over a year of time. Maybe closer to two years. Because it was a group effort, we had to meet to discuss each of our chapters and ensure the book seamlessly connected.

I feel like Middle Grade is challenging in different ways. I need to pull in so many elements to make a book feel complete. With Picture Books, I’m cutting out elements to make a book feel whole. A book feels complete when it’s concise and focused. A Middle Grade is the same in needing to be focused but there are so many elements in terms of the character arcs and plot to bring into that focus. It’s expansive and narrow, which makes it hard.

SSS: How was it to co-write a book where three other authors have distinct voices for their own three characters as well?

JTB: Co-writing was challenging but also a lot of fun. It requires a lot of communication. It helped that we had previously established friendships with each other and got along. The fun is in seeing what the other authors are doing with their characters and falling in love with these other voices. I also loved working out conflicts and creating bonds between these characters and Feek.

Bonus!

SSS: Bonus FUN question! Taking care of animals and finding a lost cat is a huge unifying factor in the book for the characters- Are you an animal lover in real life?

JTB: I do love animals! Especially cats. I don’t currently have any pets due to life circumstances but I watch cute animal videos for fun and am a member of too many Facebook cat groups.

If you liked this interview, check out this link to an article honoring Arab-American books!

Thank you so much Jamilah for answering my questions! I hope everyone picks up a copy of all your beautiful books!!

About Jamilah Thompkins-Bigelow

Jamilah Thompkins-Bigelow is a Philadelphia-based bestselling children’s book author. Her books, which center around Black and Muslim kids, have been recognized by many, including TIME and NPR, and she is an Irma Black Award silver medalist. A former teacher and forever an educator-at-heart, she is probably most proud that her picture book Your Name Is a Song was named the December 2021 NEA Read Across America book and that it is included in the curriculums of major school districts throughout the United States.

You can find Jamilah on Social Media!

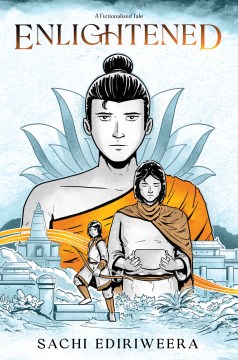

We’re excited to have Sachi Ediriweera on here today to talk about his new release. Let’s start with learning a bit more about you, Sachi, and then we’ll talk more about Enlightened.

We’re excited to have Sachi Ediriweera on here today to talk about his new release. Let’s start with learning a bit more about you, Sachi, and then we’ll talk more about Enlightened.