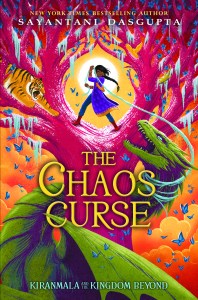

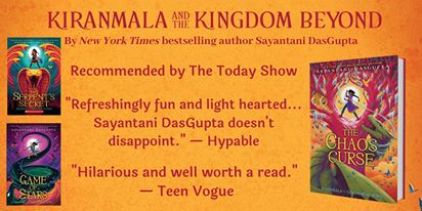

Today, I am delighted to welcome Sayantani DasGupta to Mixed-Up Files to talk about her experience writing her third book in the middle-grade adventure fantasy Kiranmala series, THE CHAOS CURSE. Sayantani’s novels feature a powerful girl character who carries a quest on her shoulders and must overcome the conflict between good and evil.

- Tell us about “The Chaos Curse,” and how your journey has been writing three novels in the Kiranmala series?

The Chaos Curse is the third in the Bengali folktale and string theory inspired Kiranmala and the Kingdom Beyond series. Kiranmala, the 12-year-old protagonist of the series, thinks she’s just an ordinary immigrant daughter growing up in New Jersey, until she realizes all her parents’ seemingly outlandish stories are true, and she really is an Indian princess from another dimension. This third and final installment of the series finds Kiranmala having to once again battle the evil Serpent King, who wants to collapse all the stories of the universe together, destroying the multiplicity of the multiverse. It is varied and heterogeneous stories, after all, which make the universe keep expanding. The Chaos Curse finds Kiranmala once again teaming up with some old friends, as well as some new ones, to try and stop the Serpent King and his nefarious Anti-Chaos Committee. Will they save the stories in time to save the multiverse?

- Your work is about a powerful twelve-year old girl Kiranmala who is proud of her ancestral heritage, connected to her family, and has a strong desire to fight for good over evil. Can you discuss how you broke stereotypes with this series?

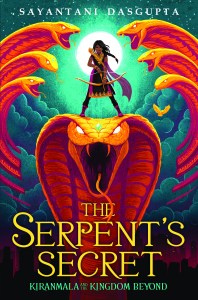

It took me many years to find an editor for The Serpent’s Secret, as ten years ago, there didn’t seem to be any room in the publishing industry for a funny, fast paced fantasy starring a strong brown immigrant daughter heroine. The answers were often similar: “We love your voice, but how about writing a realistic fiction story about your protagonist’s cultural conflict with her immigrant parents?” In other words, the story that was expected and wanted was one that reinforced stereotypes about South Asian immigrant parents (as oppressive, or regressive, or rigid) and allowed a certain type of expectation about South Asian parents and children to be fulfilled. Many marginalized communities face this narrative demand – to tell stories of conflict, stories of suffering, stories of pain – for others’ voyeuristic pleasure. But for that very reason, in our stories, joy is an important form of resistance. To portray a strong, funny Desi heroine with doting, loving parents is to break a stereotype that mainstream America has about our communities. Other ways this series breaks stereotypes is to challenge the notion of fixed good and evil altogether. For instance, the rakkhosh monsters who are pretty uniformly baddies in the first book get more nuanced in the second and third. Like any beings, there are good rakkhosh and bad rakkhosh, and Kiranmala must get over her prejudice against them, realizing that heroes and monsters are not based on family, or appearance or community, but rather, what someone chooses to do each and every day with their lives.

- In a previous interview, you shared with me that as a child, Bengali folktales were an important part of you finding your own identity. How did you personally approach storytelling in this series and make Bengali folklore accessible to young readers?

I grew up in the U.S. with very few positive ‘mirrors’ in the culture around me – not in the books I read, not in the TV shows and movies I watched. (Here, I refer of course to Dr. Rudine Sims Bishops’ important framing of books as ‘mirrors, windows and sliding glass doors.’) It was only when I would go on my long summer vacations to India that I could see heroes and heroines who looked like me – brown kids being strong and heroic, saving the day. When I thought about adapting these stories to an American audience, I was at first nervous – would I be doing these cultural stories an injustice? But then I remembered that folktales are oral stories, and as such often change in the telling. Even my grandmother would often sprinkle in her stories with little morals she wanted us grandchildren to hear on that particular day because of some naughty thing some cousin had done. So in changing and adapting the stories, I still felt like I was being true to their nature as oral folktales. Just like so many aunties and uncles and parents and grannies before me, I was simply adapting my storytelling to my audience.

- Although the story is predominantly in English, you sprinkle Bengali in the books too. Tell us about the power of weaving Bengali words into Kiranmala’s world.

I think many of us immigrant kids or Third Culture kids aren’t just multilingual, but we speak a mash-up of multiple languages at once. We speak Spanglish and Hindlish and in my case, Benglish. Sprinkling in Bengali words without apology and without italics was a way of not only honoring the language of my family and community, but reflecting the real way that so many of us communicate. I knew that non-Bengali speakers would pick up words and meaning from context, and that young Bengali readers might be seeing familiar words in an English book for the first time. That felt like a really important responsibility – and so I tried very hard to use Bengali pronunciation to guide the way I spelled these words (rakkhosh for instance instead of the more Hindi-fied “rakshas” or “rakshasa”). I also narrated the audio books myself, and tried very hard to keep to Bengali pronunciations of all these words – I wanted young listeners to hear their language pronounced correctly!

- You discussed in my previous interview that you hoped to inspire children to have radical imaginations through your stories. How has that manifested in your school visits and public readings/signings?

When I talk about radical imagination, I am usually talking about kids from marginalized communities being able to see themselves as protagonists in stories, see their own strength and heroism reflected back to them in them in books. It’s hard to be what you can’t see, right? And every kid deserves to see someone like them as a hero. But what I have found in my school visits is something else very interesting. I do meet many immigrant kids or Desi students who come up to me, hugging my books, so excited that Kiranmala is a brown kid, like them! But I also meet many non-Desi kids who are equally excited about Kiranmala’s adventures, and this feels very radical. When a gaggle of young blonde boys runs up to me telling me how much they love the series, I see something radical here too – their unquestioned ability to not just accept but cherish a strong girl as a hero, a protagonist of color. When radically representational of our todays, I truly believe that stories can help make better futures for us all by making space in all our imagings for liberatory possibilities of leadership, family and community. In other words, if you grew up reading strong brown female protagonists as a kid, it’s not such a stretch of the imagination to rally behind a strong woman of color president, right?

- What has writing this series taught you about yourself? And what advice do you have for children, young adults, and adults who want to pursue writing?

When I was in practice as a pediatrician, I used to write prescriptions for reading. This is because stories are good medicine, in all the senses of that word. This same notion brought me to Narrative Medicine, the field in which I teach. And it’s this same impulse that has pushed me to write for young people. I guess what I’ve realized is that storytelling is a critical act of healing – particularly the sort of storytelling that is filling in the narrative erasures of the past – the gaps in positive representation that so many of us suffered through. I’ve also come to realize that fantasy is an amazing way to talk about oppression, prejudice, racism, justice. But at the same time, particularly when you’re writing for young people it’s also got to be a cracking good story. Young readers are unfailingly honest. They’re not going to let you get away with lecturing them or talking down to them. They know when they’re being respected and a story is speaking with and for them.

My advice to people of any age who are writing is this – follow the joy, follow the passion. Tell the story YOU want to hear first and foremost. Don’t follow trends, or worry about publication at first. Tell the best story that only you can tell. As Toni Morrison says (and I always tell students), “If there’s a book you want to read and it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” And I truly believe each of us has the privilege and responsibility of telling our stories.

Enter the giveaway for a copy of THE CHAOS CURSE by leaving a comment below. You may earn extra entries by blogging/tweeting/facebooking the interview and letting us know. The winner will be determined on Monday, March 9th, 2020, and will be contacted via email and asked to provide a mailing address (US/Canada only) to receive the book.

If you’d like to know more about Sayantani and her novel, visit her website: http://www.sayantanidasgupta.com/writer/ Or follow her on twitter : https://twitter.com/Sayantani16

Thank you all for the comments. Lisa Springer, you are the winner of this giveaway. Congratulations! I’ll be in touch with you shortly.

I am so excited about this series as it sounds so full of action, culture, and of course your strong protagonist. Books for diverse readers have been a long time coming. I am so glad to see the marketplace begin to realize they can reach out to all people with many different visions and experiences.

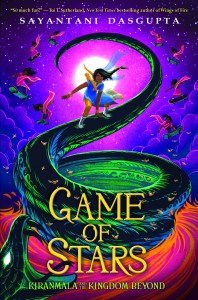

These books sounds so much fun to read. The covers are eye-catching and make me want to read these books. Thank you for the interview and chance to win a copy. I shared on tumblr: https://yesreaderwriterpoetmusician.tumblr.com/post/611850696341553152/south-asian-storytelling-author-interview-with

I’m so happy that you were able to find an editor who would print your funny, fast paced story of a strong brown immigrant daughter heroine!

Congratulations on such a great series! Diverse stories are needed now more than ever.

This response is awesome: “When I was in practice as a pediatrician, I used to write prescriptions for reading. This is because stories are good medicine, in all the senses of that word. This same notion brought me to Narrative Medicine, the field in which I teach. And it’s this same impulse that has pushed me to write for young people. I guess what I’ve realized is that storytelling is a critical act of healing – particularly the sort of storytelling that is filling in the narrative erasures of the past – the gaps in positive representation that so many of us suffered through.” I’m an English professor, and this idea will stick with me for a long time. I’m thinking of how I can adapt some of my assignments to incorporate this thought. So often, my students (teens, 20s, and older) tell me that haven’t finished a “real book” in years and years. But their storytelling might be a way in.

Yay! Congrats on such an amazing series.

I would like to read this book, thanks 😉

I love the point that joy is an important form of resistance.