I’m thrilled to introduce debut author Cindy Baldwin to our Mixed-Up Files readers today. Her new book, WHERE THE WATERMELONS GROW (HarperCollins Childrens), is set to release on July 3rd, and I am so excited!

We at MUF not only have the honor of introducing you to Cindy, but also giving you a sneak peek of her book .. a Chapter 1 reveal.

AND … because we’re cool like this … Cindy has teamed with MUF to give away a FREE copy of WHERE THE WATERMELONS GROW.

Transparency moment: Cindy and I were finalists in the Pitch Wars writing contest, so we’ve been friends for awhile. I hope you’ll look past my potential lack of objectivity and see for yourselves how great this book is.

So read on, get to know Cindy Baldwin, enjoy the first chapter of her amazing book, and then enter the Rafflecopter below to get a chance at winning your own free copy.

Interview with Cindy Baldwin

MUF: What’s the origin story for WATERMELONS?

A few years ago, when my daughter (now five) was about one, I was singing “Down By The Bay” to her. The idea of this child who’s so distressed by their mother’s mental illness that they run away from home really stuck with me, and spoke to some of my own deep insecurities and worries as a disabled parent. I knew very early on in the planning process that I wanted this to be a disability-positive book, where a kid comes to recognize that disability in her family doesn’t prevent them from having a happy, loving, positive life, and that her mother’s disability is a part of who her mother is and not something to be “fixed” or “cured.” As a disabled reader and writer, it’s really important to me that books capture the complexities and difficulties of disability honestly, but do it in a way that doesn’t paint disability either as incompatible with happiness or as “inspiration porn.”

MUF: How did you research schizophrenia – was it something you already knew a lot about?

I did know the basics of schizophrenia, like what the most common symptoms were and some of the ways it affects people in their day-to-day lives. However, I don’t have it myself, and so I wanted to do plenty of research to get it as close to “right” as I could! I spent a lot of time reading articles by psychologists as well as first-person accounts of schizophrenia from patients themselves. I had to research things like typical age of onset, how schizophrenia is affected by pregnancy and postpartum hormones (since part of the plot of my book has to do with having children when you have schizophrenia), what medication regimens are typically like, and what it might look like to have a patient slowly losing touch with reality. Although I don’t have a family member with schizophrenia, I do have some past personal experiences that gave me a little insight into some of the issues Della and Suzanne struggle with.

MUF: Why focus on schizophrenia?

I don’t have schizophrenia, but like Della’s mama, I am a disabled parent. In Where the Watermelons Grow, I really wanted to explore the idea that disability doesn’t have to be removed for characters to achieve happiness—which is a trope that pops up a lot in books with disabled characters. So often, the disability itself is the great barrier to a happy ending, and that ending can’t be achieved unless there’s a magical cure involved. When I was growing up—and even still, as a disabled adult—I found these narratives so frustrating because my health conditions are not ones that will ever go away; it was very invalidating to be shown again and again that I couldn’t have a rich, happy life while being disabled. In Watermelons, I wanted to write a book that was anti-magical-cure, showing that it’s possible to have a loving, happy, wonderful life, even if your challenges look significantly different from those of your friends.

I really wanted to explore a disability that had a very large impact on both the patient’s life and her family. I have cystic fibrosis—a life-shortening genetic disease—as well as fibromyalgia and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and my illnesses have a really profound impact on the shape of my husband’s and daughter’s lives, as well as my own. Because that’s our reality, it felt natural to write about a family, like ours, who is also greatly impacted by disability. When I was working on proofreading the manuscript, the last step before publication, I actually read it out loud to my five-year-old daughter, and it was a really neat experience to see her reactions as she listened to this story about a family whose lives weren’t all that different from ours. She picked up on a lot of the parallels as we read (she told me, “that mama has a sickness just like you, and I am just like Della!”), and we had some really cool conversations. She actually still loves to play that we are the characters from the book—I think because it is something that resonates with her own lived experience!

MUF: What challenges did you face maintaining a middle-grade voice when dealing with such a complex subject?

Della’s voice came to me so naturally that it actually wasn’t always that hard! Probably the most difficult thing was balancing the heaviness of Della’s struggle to “cure” her mother with lighter, more normal preteen activities, like hanging out with her best friend or the way her baby sister gets into trouble all the time. I also did have a bit of a tricky time knowing how much I could delve into the darker aspects of her family’s story. For instance, there are only two ways that a mentally ill person can be involuntarily committed to a behavioral health hospital (i.e., taken there without their will)—attempting to harm themselves or another person. Because Della’s mother being involuntarily committed four years previously was a big part of the plot, I had to figure out how to reference a suicide attempt, and the emotional fallout that that had on Della’s father, without it being heavy-handed or too much for young or sensitive kids. I also had to figure out how to show how Della’s daddy was fracturing at the seams himself under all the stress without it resulting in truly abusive behavior towards his kids (as it is, he engages in some definite neglect!), or showing reactions that would be too intense for readers on the younger end of the MG spectrum.

MUF: Your writing is poignant in general, but one point I found deeply resonant is the part where Miss Lorena tells Della “probably, your mama is never going to be quite like other mothers out there.” Because you live with chronic physical illness and are raising a little girl, I wondered whether that part was a little autobiographical? And if so, was it more difficult to write?

Oh, absolutely! I actually wasn’t thinking, while I was writing the book, that I was delving deep into my own insecurities about parenting as a disabled mom (it’s amazing how much the brain can ignore things it doesn’t want to face!), but a few weeks before I got an agent, a friend and critique partner asked me if I was writing my anxieties about my own daughter. My gut reaction was “No, of course not!”—but after a few seconds, it dawned on me that yes, I TOTALLY was. I’ve always had intense anxiety about parenting with a disability, since I was a teenager, actually. I worry a lot that I will never be able to give my daughter the things she needs to have a happy life. I worry that my disease will limit her. I worry a LOT about the burden of sorrow and worry that she will have to carry through her life, as my disease has some pretty serious ramifications (not unlike schizophrenia). And, like Della resents her mama at the start of the novel, I worry a lot that my daughter will grow up resenting me for what I can’t be for her. My deepest hope is that, like Della, she will both be able to be surrounded by other mothers in our community, and that she will recognize that even if I’m NOT like the other mothers out there, I still love her more than words can express and that we can still be a loving and happy family even if our family looks a little different than others.

MUF: What message do you most hope readers will come away with?

Between 11 and 13, I was grappling with a lot of more serious components of my illness, cystic fibrosis. I had stayed out of the hospital since I was two, but at 11 and 13 I was hospitalized again for the first times in my remembered life—and I had to stay all by myself through the long hospital nights because my parents were busy with newborn triplets. At 13, I also learned for the first time that cystic fibrosis is life-shortening—back then it carried a life expectancy in the mid-30s. These big, difficult life experiences often felt overwhelming and isolating at that age. I felt different from everyone around me like I was living on a completely different frequency than the rest of the world, and nobody quite understood what I was going through. In so many ways, I wrote WATERMELONS for my preteen self, the one who felt so at odds with her peers; I wanted to write a book for all the children whose lives look different from their friends. This book is like my love letter to those children—to the child I was. I hope that they come away from WATERMELONS with the firm conviction that even if their lives might look different, they can still be rich, happy, and satisfying. I also hope that children and adults emerge from WATERMELONS ready to treat disabled people with a little more dignity and acceptance, something that our society could really use!

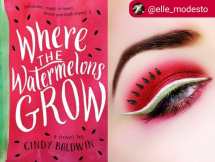

MUF: You’ve had so much fun with your watermelon theme – people have posted pictures on Instagram and Facebook with watermelons and other book-themed layouts; one friend even posted a picture of her baby girl wearing a watermelon dress. What are some of your other favorite fan-stagrams?

Oh man. I have to choose just a few?! It delights me to no end when people share their watermelon ideas with me. It’s seriously been a highlight of this whole lead-up to publication! Some of my favorite things I’ve done:

Author and makeup artist extraordinaire Michelle Modesto created the most INCREDIBLE eye makeup look based on the cover for WHERE THE WATERMELONS GROW.

One night, I showed up for a weekly family dinner at my parents’ house and discovered that my dad and sister had made me a watermelon cake, just for fun! It was darling and delicious, too.

One of my dear friends who knows how much I love dahlias sent me a pair of dahlia tubers for a variety called Penhill Watermelon. I can’t wait to see them grow!

And almost more than anything, I’ve been so touched by reviews from teachers and librarians that have been shared with me on social media. It’s amazing to see this book that has lived in my head for so long really making an impact in other peoples’ lives.

MUF: We as authors often share at least one trait with our main characters. Is your favorite food watermelon?

I can’t say it’s my ONLY favorite, because I have a LOT of favorites! And in general, I love the abundance of fresh fruit in spring, summer, and fall. I live in Oregon and from May to September I pretty much live my life by what delectable fruit is in season! But watermelon is and always has been one of my absolute favorite parts of summer, just like it is for Della. Ever since I was a little kid, there’s been nothing that screamed “summer” more than a cool watermelon bursting with juice! The part in the book where Della says that she likes to reach into the fridge and just take big spoonfuls right from the watermelon is 100% something I do and have gotten in hot water with family members over! And once in college I really did sit down at the table and eat an entire watermelon, just like Della claims she can do. Basically, if you set me up with some watermelon and summer sweet corn, I’d be perfectly happy for the months of July and August.

Cindy Baldwin is a fiction writer, essayist, and poet. She grew up in North Carolina and still misses the sweet watermelons and warm accents on a daily basis. As a middle schooler, she kept a book under her bathroom sink to read over and over while fixing her hair or brushing her teeth, and she dreams of writing the kind of books readers can’t bear to be without. She lives in Portland, Oregon with her husband and daughter, surrounded by tall trees and wild blackberries. Her debut novel, Where The Watermelons Grow, was named an Indies Introduce/Indie Next pick for 2018, as well as receiving starred reviews from School Library Journal and Booklist.

First Peek: WHERE THE WATERMELONS GROW

CHAPTER ONE

On summer nights, the moon reaches right in through my window and paints itself across the ceiling in swirls and gleams of silver.

I lay in bed, the sheet on top of me as hot and heavy as a down quilt, listening to the roar of the box fans that

weren’t doing a single thing to keep the heat out of my bedroom. I’d gone to bed hours earlier, but it was too hot

to sleep—too hot to do anything but lie there watching the moonlight shift across the ceiling, thoughts spinning

through my head like the wind on the bay right before a storm breaks. On the other side of the room, baby Mylie

snored in her crib.

Only a baby could sleep on a night as hot as this.

I closed my eyes, letting a string of numbers appear against my darkened eyelids. Doubling numbers as far

up as I could go: it was a trick Daddy had taught me, and my favorite way to fall asleep—a problem interesting

enough to keep my mind focused, but not so hard that I couldn’t drift off when I was ready. One. Two.

Four. Eight. Sixteen. Thirty-two. Sixty-four.

I’d made it all the way to One thousand twenty-four times two is two thousand forty-eight when I finally gave

up trying to concentrate my way into sleep and slid my legs over the side of the bed, the cool carpet hitting my

toes a tiny little shot of relief in all that heat. The clock on my nightstand read 12:03. I tiptoed out of my bedroom

and through the dark hallway so nobody could hear I was awake and come tell me off for it.

But I wasn’t the only one awake.

Mama was sitting at the kitchen table, her pale skin strange and greenish in the light from the left-open

fridge. A plate of watermelon slices sat on the table in front of her, and she was looking at them with the same

look I have when I’m taking a test in English class. She sed the tip of a knife to flick the black seeds out of each

slice, one by one, not seeming to care that they were landing all over the table and the floor. One seed had

stuck itself to her forehead, hanging there like a little bug just above her crunched-up concentrating eyebrow.

“Mama?” My voice was quiet and a little shaky in the silent kitchen, with only the refrigerator hum to back

me up.

It was one of Daddy’s sliced-up watermelons on that plate. My daddy grows the sweetest watermelons

in all of North Carolina. He grows other things, too, like wheat and peanuts in his big fields and squash and

berries in his small ones, but the watermelons are my favorite. Biting into one of those ruby-red slices is like

tasting July, feeling that cold juice hitting your tongue like an explosion.

I like to take a spoon and dig out round bites so big they barely fit into my mouth, but Mama’s always after me to slice them in neat little pyramids. “So that everyone can enjoy them,” she says, glaring at the holes my spoon left, and every time she does I know she’s thinking about all the germs that came from my lips touching that spoon touching the watermelon.

But whatever she was doing to those slices on that plate was way worse than obsessing over a few germs. Watermelon is near about my favorite thing in the world to eat—if I’m hungry enough, I can eat almost a whole one by myself, which Daddy says is pretty impressive for a girl who’s barely twelve and not yet five feet tall—but right then, the taste of all those remembered melons on my tongue was sour and awful.

I cleared my throat. “Mama?” I said again, louder this time.

“Della,” she said. “You oughta be in bed.”

“I just had to get a drink of water.” I wiggled my toes against the bare linoleum floor. It was sticky where it

hadn’t gotten cleaned up enough after Mylie threw her sippy cup down there when she pitched a fit about going

to bed.

Where sleeping was concerned, Mylie pitched a lot of fits.

“What are you doing, Mama? Don’t you want to be in bed, too?”

“No.”

I inched into the kitchen a little at a time, keeping my feet away from the seeds all over the floor and reaching

for a clean glass from the cupboard. I ignored the open fridge with Mama’s special no-germs-here water-filtering

pitcher and filled my cup with tap water from the sink. I didn’t want to know what Mama was doing. It felt like

the long-ago bad time all over again, and I didn’t want to know a single thing more about any of it. So all I said

was, “Do you know you got a watermelon seed stuck above your eye?”

Mama’s fingers flew to her forehead, picking the seed off and flicking it onto the tabletop real quick, like it might bite her. “I don’t like these. There’s just too many of them. I don’t want you eating any, okay? And I don’t want you feeding them to Mylie, either. I don’t want them crawling around in your tummies and making you

sick.”

The glass of water froze in my hand halfway to my mouth. I looked at Mama and looked at her some more,

wishing so hard that I hadn’t gotten out of bed in the first place. Wishing I was asleep like I should have been,

so that I wouldn’t be here seeing Mama acting like this.

I drank up all my water and put the cup in the sink. Sometimes I liked to put my water cups on the counter,

so I could keep drinking out of them and didn’t have to wash them out between, but anytime I did that, Mama

got on my case about all the germs my mouth had left on there. I never knew what she thought was going to

happen—it wasn’t like those mouth germs were going to crawl down the sides of the glass and onto the counter—

but she sure didn’t like for me to leave them.

“Listen,” I said, taking a deep breath and pretending I was talking to Mylie instead of to Mama. More than

anything I just wanted to go back into my bed and close my eyes and pretend I’d never come in here in the first place, but I knew I couldn’t do that without it eating me up from the inside. Mama needed me. “I’m gonna close

the fridge door now, okay? And then I’m gonna help you clean up the watermelon, and I think you should go to

bed, otherwise you’ll be tired at church tomorrow. And I know you don’t like that.”

What Mama really didn’t like was when I was tired at church, but she didn’t like being tired herself, either,

because she said it turned her into a mean-green-mama-monster.

Sure enough, Mama frowned. “Why are you still up, Della?” she asked, like I hadn’t just told her a minute

ago. “You need to be in bed, honey.”

I sighed. “I know. I’m going there right now. You gonna come to bed, too?”

Her eyes snapped back to that plate of watermelon, and her fingers started up again with the knife. The

seeds made wet little taps on the table as they hit it, tap-tap-tap-tap-tap. “No!” she said, and I felt my shoulders

jump a little, because she was so loud she was almost yelling. “I can’t go to sleep tonight. I need to take care of

this watermelon.”

I heard a door open down the hallway, and Daddy came out, looking tired. His feet were bare and his hair

was sticking up all over his head.

“Suzanne,” he said, “what’s the matter?” Then he saw me. “Della, what are you doing out of bed? You know it’s

after midnight, right?”

I sighed again, a loud one this time so that Daddy could hear it. “I was just getting a drink.” It was Mama I

was mad at, but I couldn’t stop that mad creeping across the kitchen toward Daddy anyway. “Is that not allowed

in this house anymore?”

“Don’t sass,” said Daddy, but he didn’t sound upset. He never sounded upset. That’s one of those things about

my daddy—he’s so calm and quiet that you can hardly hear him talk sometimes. “Did you get your drink?”

“Yeah. Good night.”

I didn’t look at Mama again, but I could still hear those watermelon seeds tap-tap-tapping on the table as I

walked down the hallway.

“Suzanne, please come to bed now,” Daddy said as I opened my bedroom door.

“Can’t. Can’t go to sleep. Too busy.”

There was silence behind me. I pictured Daddy pushing his callused white fingers through his brown hair

like he does when he’s upset and can’t figure out what to do about it. “Suzie,” he said, and his voice was so quiet I

could hardly hear it, “you need your sleep, sweetie. You know you need your sleep or you’re gonna get sicker.”

Mama didn’t say anything. I pulled my bedroom door closed behind me carefully and slowly, leaving it open a crack by my ear, so I could still hear them.

“Suzanne. Come with me now, all right? Come on to bed, please.”

“No!”

I swallowed. Mama was almost-yelling at Daddy just like she’d been almost-yelling at me. I peeked through

the crack I’d made in my doorway and could just barely see him, there behind Mama with his hands on her elbows, trying to pull her up out of that chair.

“Suzie, sweetie, put that knife away.”

“No!” Mama shouted again, louder this time. From the other side of the bedroom, Mylie started whimpering and shaking the bars of her crib.

“Leave me alone,” Mama said. “Just leave me alone. I have to do this. It’s important. I gotta keep the girls

safe.”

I tiptoed over and reached through the crib bars to put my hand on Mylie’s head, feeling her soft strawberry-blond

curls all wet from sleep sweating. She was sitting up, her fat fingers in fists around the bars.

“Shh,” I whispered, and she quieted down. “It’s all right, baby. Go back to sleep. You want I should tell you

a Bee Story?”

“Stowy,” Mylie repeated, wiggling her little body till she was lying back down on the mattress.

“All right,” I said, sinking down on to my knees by the crib, my voice still quiet and low. I reached my hand

in through the crib bars and rubbed her back as I spoke. I could feel her start to settle, relaxing into the mattress,

like my hand on her back was all she needed to feel safe. Lucky baby. “Way back a long time ago, when Grandpa

Kelly was still a little boy and the farm belonged to his daddy, he was playing on the tractor when he fell off and got a big old cut right down his leg. It was long and deep, and his parents knew if they took him to a doctor it would need stitching and medicine and might never heal good enough for him to walk normal. So they didn’t take him to a doctor. They took him to the Quigleys.”

I leaned my face against the crib, feeling the bars cool and hard on my skin. Mylie’s breathing was steadying, but I could still see the shadows of her open eyelids there in the dark.

“It wasn’t our Bee Lady who was living there then, of course. It was her grandma. Grandpa Kelly asked Mrs. Quigley if her bees had anything that might fix up Grandpa’s leg. Mrs. Quigley took one look at that big old gash, and at Grandpa’s face white as cotton fluff, and went right to her shelves for one of her honeys. It was dark and sticky and thick, and when she tipped the jar over Grandpa’s leg, it took a long time to roll its slow way out. Mrs. Quigley spread it all over Grandpa’s cut with her gentle hands.”

Now Mylie’s eyes were closed, her little butterfly lashes soft against her cream-colored cheek. I slid my hand off her back and she didn’t stir.

“And Grandpa’s leg healed so fast and so clean there was hardly even a scar, and he was up and walking by the time the sun set that day,” I whispered to myself, and then walked back over to my bed and climbed into it, lying down on top of all my blankets. It was too hot for them, anyway.

It was a true story, that one about Grandpa and his leg. More than once, he’d shown me the thin white line of scar tissue that ran almost from knee to ankle. If there hadn’t been a Bee Lady in Maryville, he always said, he probably would’ve limped through the rest of his life.

I sighed and rolled over. Daddy had gone back into his bedroom while I’d been talking to Mylie, but if I listened real hard, I could still hear those seeds tap-tap-tapping on the kitchen table.

I closed my eyes, trying to forget all about those watermelon seeds, all about Mama yelling and acting worse than she had in a long, long time, wishing there was anything in the world that could pull Mama’s brain back together like the skin on Grandpa’s leg.

Fixed right up, without anything more than a harmless little scar.

###