STEM Tuesday–Symbiosis– Interview with co-authors Jenn Dlugos and Charlie Hatton

Welcome to STEM Tuesday: Author Interview & Book Giveaway, a repeating feature for the last Tuesday of every month. Go, Science-Tech-Engineering-Math!

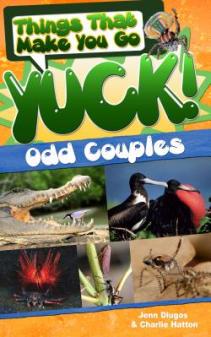

Today we’re interviewing authors Jenn Dlugos and Charlie Hatton, co-authors of Odd Couples, part of their “Things That Make You Go Yuck” series. Although busy with lots of projects–Jenn writes and illustrates science text books, and Charlie is a computational biologist–they say they collaborate on their books to meet a “fundamental ‘need’ to be creative.” Self-proclaimed science nerds who met through stand-up comedy, they bring humor to their books. In a time when basic biology has revealed its scary side, it’s a relief to be able to laugh a little while enjoying the fascinating tales of interrelationships in this book.

(*I had a lot of questions and Jenn and Charlie had a lot to share. This interview has been edited for brevity.–CCD)

Carolyn Cinami DeCristofano: What’s Odd Couples about—and what was most important to you in deciding to write it?

CH: Odd Couples is part of a series of “Things That Make You Go Yuck!” books, all about interesting and unusual critters and plants. This book explores some of the cooperative – and competitive and completely bonkers – relationships between organisms. With Odd Couples and all the Yuck! Books, we wanted to show young readers that even the “yucky” bits of nature can be fascinating, inspiring and sometimes oddly beautiful.

JD: Every second is life or death in the wild, and sometimes organisms have to work together to survive. Odd Couples covers everything from weird mating habits to strange friendships (and frenemy-ships). From a crab that waves sea anemones around like pom poms to ward off predators to sloths that have strange friendships moths that lays eggs in sloth poop, Odd Couples covers the oddest of the odd.

CCD: You are two co-authors of a book named Odd Couples, so of course I have to ask: What kind of an odd couple are you? How would you describe your creative partnership?

CH: Oh, we’re odd. We met around fifteen years ago doing amateur standup comedy around the Boston area among a crowd of fellow misfits. We began collaborating on creative projects a few years ago, which has turned out to be much more productive than telling jokes at a coffee shop at midnight on a Tuesday. We’ve taken a “sure, let’s try it” approach to projects, leading to working together on writing books as well as short plays, producing a web series and short films, and various other oddities-in-progress.

JD: In biological terms, we’re in a parasitic relationship. The parasite is whomever is not paying the tab that week.

CCD: What’s one of your favorite organism relationships from the book? Why is it a favorite?

CH: We researched a number of parasites for Odd Couples, which is a really… interesting way to spend your Saturday afternoons. My favorite is a flatworm called Ribeiroia that infects frogs during one phase of its life cycle. The worms’ next stage of development occurs in birds. To improve their odds of getting there, the worms affect infected frogs’ development, causing them to grow extra, gangly useless legs that hinder their hopping. These frogs are less likely to escape birds trying to eat them, which is good for the worms – though not as much for the Franken-frogs. It’s basically a Bond movie villain strategy for getting ahead.

JD: My favorite animals are spiders. (Yes, really. I had pet tarantulas when I was younger.) So, I have to go with the peacock spider. It’s an adorable little arachnid who basically does the Y.M.C.A. dance to attract a mate. Scientists recently discovered a new species of peacock spider that has markings that resemble a skeleton. You know, because spiders need to double-down on their creepy reputation.

CCD: Can you say a little about how your writing partnership works? For example, who does what when?

CH: On most projects, we discuss an outline and detailed plans for writing. I promptly forget most of it, and Jenn reminds me of the parts she says that we both liked the best. It’s not the most efficient process, but it works. While writing, we generally pass material back and forth – in the case of Odd Couples, we agreed on a format and researched the organisms we wanted to include, then split them up to each write about our favorites. Sort of like a fantasy sports draft, only with more spiders and parasites.

JD: Nothing happens until food and drinks arrive. It’s very possible that our waiter/waitress is our muse. Several hours later, we have something that resembles an outline typed out in Jenn-ese on my phone. I translate it to something that resembles English, and from there it’s a 50/50 split. We’ve been writing together for so long that we’ve developed a joint voice, and we sometimes forget which part each of us wrote. There have been more than a few times we have seen/heard a joke in something we’ve written and wondered which one of us was responsible for that nonsense.

CCD: What’s next for you as authors?

JD: Another infographics book (is) waiting in the wings after Awesome Space Tech.

(Awesome Space Tech, also an infographics project, is Jenn and Charlie’s latest book. –CCD)

CCD: Well, I’d bet that your humor and serious science creds have led to yet another book that will inspire, entertain, and fascinate kids. Your symbiosis certainly benefits others! Thanks so much for your time!

Win a FREE copy of Odd Couples

Enter the giveaway by leaving a comment below. (Scroll past the link to the previous post.) The randomly-chosen winner will be contacted via email and asked to provide a mailing address (within the U.S. only) to receive the book.

Good luck!

Boston-based collaborators, Jenn Dlugos and Charlie Hatton are co-authors of Prufrock Press’s series, “Things That Make You Go Yuck!” and, in Charlie’s words, “several other, far more ridiculous projects.”

By day, Jenn writes science textbooks, assessments, and lab manuals for grades K–12. By night, she writes comedy screenplays, stage plays, and other ridiculous things with Charlie Hatton. Her favorite creepy crawlies are spiders.

Charlie is a bioinformatician who slings data for a cancer research hospital–as well as a science fan and humorist. He enjoys working with genetic and other data to support cancer research, learning about new and interesting scientific areas, and referring to himself in the third person in biographical blurbs.

***

Carolyn DeCristofano, a founding team member of STEM Tuesday, is a children’s STEM author and STEM education consultant. She recently co-founded STEM Education Insights, an educational research, program evaluation, and curriculum development firm which complements her independent work as Blue Heron STEM Education. She has authored several acclaimed science books, including Running on Sunshine (HarperCollins Children) and A Black Hole is NOT a Hole (Charlesbridge).

Carolyn DeCristofano, a founding team member of STEM Tuesday, is a children’s STEM author and STEM education consultant. She recently co-founded STEM Education Insights, an educational research, program evaluation, and curriculum development firm which complements her independent work as Blue Heron STEM Education. She has authored several acclaimed science books, including Running on Sunshine (HarperCollins Children) and A Black Hole is NOT a Hole (Charlesbridge).

Welcome to STEM Tuesday: Author Interview & Book Giveaway, a repeating feature for the fourth Tuesday of every month. Go Science-Tech-Engineering-Math!

Welcome to STEM Tuesday: Author Interview & Book Giveaway, a repeating feature for the fourth Tuesday of every month. Go Science-Tech-Engineering-Math!

Your host this week is fellow tree freak

Your host this week is fellow tree freak