If you’ve read Jacqueline Woodson’s Brown Girl Dreaming, or Kwame Alexander’s The Crossover, or Laura Shovan’s The Last Fifth Grade of Emerson Elementary, or Margarita Engle’s The Surrender Tree — or any other beautifully crafted novel in verse — you know how powerful this form of the written word can be. Here, five authors of middle-grade verse novels, Thanhhà Lại, Chris Baron, Aida Salazar, Skila Brown, and Ellie Terry, share their love for the genre…and why verse speaks to them in ways prose can’t.

Meet the authors and their books:

T

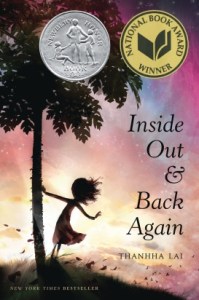

T hanhhà Lại is the New York Times bestselling author of INSIDE OUT & BACK AGAIN (2011), her debut novel in verse, which won both a National Book Award and a Newbery Honor. Praised by Kirkus as “poignant and unexpectedly funny,” INSIDE OUT & BACK AGAIN is inspired by Lại’s experience as a refugee, fleeing Vietnam after the Fall of Saigon and immigrating to Alabama. Lại’s other books include the YA debut BUTTERLY YELLOW (HarperCollins, 2019), and LISTEN, SLOWLY (2015), a Publisher’s Weekly Best Book of the Year. Learn more about Lại on her website.

hanhhà Lại is the New York Times bestselling author of INSIDE OUT & BACK AGAIN (2011), her debut novel in verse, which won both a National Book Award and a Newbery Honor. Praised by Kirkus as “poignant and unexpectedly funny,” INSIDE OUT & BACK AGAIN is inspired by Lại’s experience as a refugee, fleeing Vietnam after the Fall of Saigon and immigrating to Alabama. Lại’s other books include the YA debut BUTTERLY YELLOW (HarperCollins, 2019), and LISTEN, SLOWLY (2015), a Publisher’s Weekly Best Book of the Year. Learn more about Lại on her website.

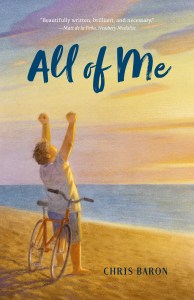

Ch ris Baron, a poet, and professor of English at San Diego City College and director of the Writing Center, is the author of the novel in verse, ALL OF ME (Feiwel & Friends/Macmillan, 2019). Described by Booklist magazine as “[A] beautifully written and psychologically acute debut,” ALL OF ME follows 13-year-old Ari Rosensweig on a journey of self-acceptance as he battles with his weight, self-harm, and bullying; witnesses his parents’ rocky marriage; and deals with his burgeoning feelings of attraction for his elusive friend, Lisa. Learn more about Baron on his website and follow him on Twitter and Instagram.

ris Baron, a poet, and professor of English at San Diego City College and director of the Writing Center, is the author of the novel in verse, ALL OF ME (Feiwel & Friends/Macmillan, 2019). Described by Booklist magazine as “[A] beautifully written and psychologically acute debut,” ALL OF ME follows 13-year-old Ari Rosensweig on a journey of self-acceptance as he battles with his weight, self-harm, and bullying; witnesses his parents’ rocky marriage; and deals with his burgeoning feelings of attraction for his elusive friend, Lisa. Learn more about Baron on his website and follow him on Twitter and Instagram.

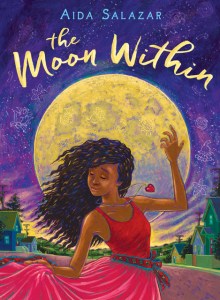

Aida Salazar is a writer, arts advocate, and home-schooling mother whose writings for adults and children explore issues of identity and social justice. Her MG debut novel in verse, THE MOON WITHIN (Scholastic, 2019), was hailed by Kirkus as “a worthy successor to Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret” and the first-middle grade novel to reflect menstruation from the Latinx perspective. Salazar’s forthcoming novel, THE LAND OF THE CRANES (Fall, 2020), and picture book JOVITA WORE PANTS: THE STORY OF A REVOLUTIONARY FIGHTER (Spring, 2021), are also published by Scholastic. Salazaar lives with her family in Oakland, CA. Learn more about Salazar on her website and follow her on Twitter.

Sk ila Brown is the author of verse novels CAMINAR (2014), inspired by events during Guatemala’s 1981 civil war, and TO STAY ALIVE (2016), told from the viewpoint of one of the members of the Donner Party and described by Horn Book as “a nuanced and haunting portrayal of the indomitable human spirit.” Her two books of poetry, SLICKETY QUICK (2016) and CLACKETY TRACK (2019), are also published by Candlewick. Brown, who received an MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts, grew up in Kentucky and Tennessee and now lives in Indiana where she writes books for readers of all ages. Learn more about Brown on her website.

ila Brown is the author of verse novels CAMINAR (2014), inspired by events during Guatemala’s 1981 civil war, and TO STAY ALIVE (2016), told from the viewpoint of one of the members of the Donner Party and described by Horn Book as “a nuanced and haunting portrayal of the indomitable human spirit.” Her two books of poetry, SLICKETY QUICK (2016) and CLACKETY TRACK (2019), are also published by Candlewick. Brown, who received an MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts, grew up in Kentucky and Tennessee and now lives in Indiana where she writes books for readers of all ages. Learn more about Brown on her website.

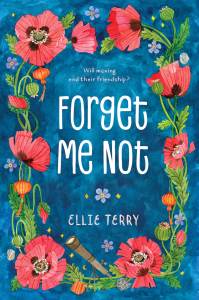

Ellie  Terry is the debut author of FORGET ME NOT (2017, Feiwel & Friends/Macmillan), a novel in verse that centers on astronomy-loving Calliope June, a 12-year-old who struggles with Tourette syndrome—all the while navigating seventh grade at a new school, in a new town. A novel of self-acceptance and the meaning of friendship, School Library Journal hailed Terry’s debut as one that “will stay in the hearts and minds of readers for a long time.” She lives in southern Utah with her husband, three kids, two zebra finches, and a Russian tortoise. Visit Terry’s website and follow her on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Terry is the debut author of FORGET ME NOT (2017, Feiwel & Friends/Macmillan), a novel in verse that centers on astronomy-loving Calliope June, a 12-year-old who struggles with Tourette syndrome—all the while navigating seventh grade at a new school, in a new town. A novel of self-acceptance and the meaning of friendship, School Library Journal hailed Terry’s debut as one that “will stay in the hearts and minds of readers for a long time.” She lives in southern Utah with her husband, three kids, two zebra finches, and a Russian tortoise. Visit Terry’s website and follow her on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

And now, without further ado, the questions…

MR: Authors, your debut novels are written in verse. What is it about this form that appeals to you?

Thanhhà Lại: I struggled for years writing in prose about a refugee family. Still, the voice never rang true because my long sentences couldn’t convey what it’s like to think in Vietnamese. Once I found prose poems, where sentences were broken into a cadence and where images could be infused into thoughts, I knew I had happened upon the best way for English words to land on a page for my characters.

Chris Baron: Poetry speaks to the heart. We see with more than just our eyes, and the music of poetry helps words sing directly to us. I have always loved the way poetry says more with less; the way the images evoke the emotion in unexpected ways that are sometimes stunning, sometimes subtle. Personally, I feel the most comfortable writing poetry. I don’t think the world always flows in a linear way all the time anyway, so the idea of finding the right imagery and language to explore what is going on around us, and then articulating the images we see in order to convey meaningful emotion and connection, is a very powerful way to discover stories.

Also, I am drawn to images, and I love the idea that a single image can be foundational to a story. I have always been someone who records things, images, and ideas. When I was a middle grader, I was captured by the Narnia stories–and then I read this C.S. Lewis Quote: ‘The Lion all began with a picture of a faun carrying an umbrella and parcels in a snowy wood. This picture had been in my mind since I was about sixteen. Then one day, when I was about forty, I said to myself, ‘Let’s try to make a story about it.'” Something clicked for me then, and I thought: I better write stuff down because you never know when a simple image might become the next story!

Aida Salazar: The first pages I wrote came in verse and in my main character Celi’s voice as clear as day. I had recently read Andrea Davis Pinkney’s verse novel, The Red Pencil. It reminded me to trust my origins as a poet. I remembered that poetry, like love, is powerful and deepens the meaning in our lives. The story I wanted to tell about the blossoming of brown and queer kids lent itself perfectly to the form. I followed the muse in this way until I finished the manuscript.

Poetry is my manantial, the spring from which all my writing flows. Though I also write prose, I always aim for my prose to be infused with poetry and lyricism. This is the kind of writing I like to read and find most intriguing — writing that is rich in metaphor, imagery, and unusual phrasing; writing that enters the emotional essence of a character to show us a truth about humanity that we don’t often see. I love verse novels for these very same qualities. There is a tension at play between elements poetry gives us (economy of words, metaphor, simile, line breaks, white space, etc.) and the standard elements in crafting a story (conflict, plot, character arc, etc.). I love the hybridity of this space. I love this tension. With verse novels you can’t spend too much time waxing poetic because you do have a story to tell but you can bring the poetic point of view into every speech, action and plot point as you go. Verse novels are a wonderful space from which to tell a story that is unique, vulnerable and compelling at once.

Skila Brown: I think poetry is a great way to narrate something that’s hard to digest. Starvation and genocide are tough topics for any reader. Using a poet’s tools, such as white space and symbolism, allow readers of all ages to process what they are able to process in a way that suits them best. Poetry makes these stories more accessible.

Ellie Terry: I love working with words on a smaller scale and getting to literally play with them and arrange them however I want; you know, being able to show readers how the story develops in my brain.

MR: What are the biggest challenges of writing in verse? The biggest rewards?

Thanhhà Lại: I naturally think in verse because I grew up listening to my mother recite poetry all day. That is how she talks. It is much easier for me to write in prose poems. The challenge lies in using verse for characters who are not thinking in Vietnamese. I haven’t found a way to do that yet.

Chris Baron: I think there are practical challenges. While there are the core elements of fiction at work, plot, character setting, etc., they don’t always function in a traditional way. Dialogue, for example, can often feel uneven compared to the internal thoughts. Or, form… I like to use free verse, but I use many different poetic conventions: syllabics, figurative language, accentual meter. This is all joy, but it can also be challenging because if it isn’t measured or cared for, it can create a sort of anti-rhythm that challenges the reader in an unwelcoming way. I have to spend a lot of time crafting and “performing” the poem out loud to hear the cadences and breaths in the writing. Each poem (or section) must be strong enough to stand on its own. This is true for any chapter, but there is a lot of pressure on the already compressed and concise words in a novel in verse, so even though fewer words are being used, this can sometimes take a lot of time.

I think there is a lot of power in the idea that author is not only focusing on the use of words but also use of all the empty space on the page. Every part of it matters, so authors writing in verse contend with the entire page, the placement of words, and how they come together everywhere. Also, the form allows for the reader to hopefully jump right into the action since the language is so concise. I try to make sure that every poem carries its weight, moves the story, can stand alone, and supply value for the reader–not just in the overall story, but in the immediate moment of reading that specific poem.

Aida Salazar: The challenge in writing a verse novel is to synchronize story and verse so that one does not overshadow the other; to craft them in such a way that they dance beautifully together. In my process, after the initial draft of the story is done, I go back and ask myself a series of questions pertaining to poetry. What is the rhythm of the line? Is there metaphor? Is there figurative and unusual use of language? How do the lines break? Do the line breaks serve the piece? Do the lines perform the text…? When I’ve answered all of these questions exhaustively, and made corrections and enhancements, that is where I find the biggest reward.

Skila Brown: I think dialogue in verse is tricky. Most of us don’t authentically speak in poetic ways in everyday conversation, so writing what our character says aloud can be tough. The biggest reward of writing verse novels for me is definitely hearing from teachers how much reluctant readers and ENL students lovereading verse novels. The smaller word-count and quick page-turns go a long way to keep some readers engaged in the story.

Ellie Terry: The biggest challenge/frustration for me is revision. When writing regular prose, I can easily remove/rearrange words, sentences, but when I’m working with verse, changing just one word often affects the entire stanza/page/poem and then I have to re-work everything. The biggest reward is when a poem comes together to explain exactly how the character is feeling . . . and it hits the reader in the heart.

MR: Somehow, the novel-in-verse form is able to capture characters’ emotions in a way that prose often cannot. What is it about this form that strikes such an emotional chord with the reader?

Thanhhà Lại: Fewer words loaded with images. I combed through INSIDE OUT & BACK AGAIN and deleted every unneeded word, much like boiling gallons of sap to get a pint of syrup. Without having to wade through a dense fog of sentences, readers can breathe and feel the words allowed on a page.

Chris Baron: There is room in a poem to be raw, vulnerable, and completely imperfect. I think that the novel-in-verse form creates an intimacy with a reader that is immediate, personal, and allows them to hear the tone and cadence of a character’s voice. I think this can create even stronger connections for readers because the form provides greater access to the internal landscape of a character. Poetry also relates to all kinds of readers. There is space on the page, measured breaks, pacing, music, and movement of lines that a reader of almost any level can find their way into. The imagery in a poem is not just about giving the setting but about the way the setting directly interacts and connects with characters’ minds, actions, and emotions.

Aida Salazar: As with all writing, the relationship between the reader and the text is ultimately personal. The power of story is profound. However, with verse, a more intimate layer is accessed because it is one focused on artistry. Through selective and precise language, the poet brings the reader into feelings and thoughts such as a vivid childhood memory, a trivial or deep idea about the world, the helplessness of falling in love, or a struggle with the spirit. The goal is not only to communicate a conflict and a plot but to create art that ignites the senses and the heart and speaks to the humanity in us all.

Skila Brown: I think dialogue in verse is tricky. Most of us don’t authentically speak in poetic ways in everyday conversation, so writing what our character says aloud can be tough. The biggest reward of writing verse novels for me is definitely hearing from teachers how much reluctant readers and ENL students lovereading verse novels. The smaller word-count and quick page-turns go a long way to keep some readers engaged in the story.

Ellie Terry: This kind of goes along with what I was saying above. Poetry is meant to make the reader feel an emotion. If it doesn’t make the reader laugh, cry, get angry, jealous, feel like they got punched in the gut, etc. it isn’t poetry. Also, you know that saying, “Sometimes less is more?” I think that’s true for verse novels. Sometimes less words = more emotional impact.

MR: What advice would you give to aspiring writers of novels-in-verse? Does one need a background in poetry to write one?

Thanhhà Lại: I didn’t study poetry. I don’t call myself a poet. I write inside a character and if prose poems represent an authentic way to convey that character’s thoughts, then I write in verse. So I am not the best person to detail the preparations involved in a poet’s craft.

Chris Baron: So many kidlit authors have incredibly poetic, lyrical lines in their prose, so the gap isn’t always that wide. I think what has helped me the most is to read novels-in-verse, learn from what master authors like Jacqueline Woodson, Margarita Engle, Joy McCullough, Nicky Grimes, Thanhhà Lại, Kwame Alexander, and others. It always helps to be in a writing community that appreciates and understands the genre. And, I think taking a class or a poetry workshop never fails to inspire, and at the very least, help us to produce more work!

Skila Brown: To me, a “background in poetry” is really about experience with poems. If you’re wanting to write a verse novel, you should obviously read some of the great verse novels that are out there. Lots of them. But you should also spend time absorbing poems. Poems that rhyme. Poems that don’t. Poems for small children and poems for pretentious adults. Songs are great to study too, not just for the lyrics but also for the sound of putting it all together. Hearing the words beat out a rhythm in your soul—that’s poetic training.

Ellie Terry: I don’t think it’s necessary for an aspiring verse novelist to have a background in poetry, but it would certainly be beneficial! Verse is so much more than adding random line breaks to regular prose. It’s about creating white space and directing the readers’ attention to specific words. It’s about syntax and using poetic techniques such as alliteration and metaphors. Reading published verse novels and becoming familiar with poetic devices would be a great place to start!

MR: Thanhhà, Chris, and Ellie: Your debut novels are loosely autobiographical. What are the main differences between you and your protagonists? The similarities?

Thanhhà Lại: Hà [in INSIDE OUT & BACK AGAIN] and I both were born in Vietnam and dropped at age ten into this strange land called Alabama. We both have fathers missing in action. Our mothers are especially similar. Fictional Hà is much spunkier than I ever was. She envisions an upward trajectory within one year whereas it took me a decade to feel like I will be fine. And she’s much funnier. I don’t remember being funny. Mostly I stood alone and shot laser eyes at everyone while trying to make sense of life among Alabamians.

Chris Baron: Ari [in ALL OF ME] is definitely a character born from my experiences, both internally and externally. Like Ari, I have an artist mom, and my parents were just very busy parents. And I had to deal with my weight issues. I had a lot of fun growing up, but it was really hard. I think Ari learns a lot faster than me, though, and he does a good job of listening and learning from his friends. I wish I had done that. Also, I think Ari is really brave. (I’m working on that too.) The other side of Ari is that he is more of a gentle soul, and I’ve known so many kids like this growing up; kids who would adventure, take risks, challenge themselves, but don’t necessarily want to step on anyone as part of it. I wanted to give some voice for them too.

Ellie Terry: FORGET ME NOT is definitely a work of fiction; however, I did use parts of my life (especially the tics and compulsions and the feelings that go along with those) and incorporate them into the novel and into my main character, Calli. We have a lot in common, but we have a few differences too. For example, Calli is an only child, while I have seven siblings! Calli is also much braver that I was at her age.

MR: Skila: You have published two books of poetry as well. Do you feel as if you need to inhabit a different headspace to write poems?

Skila Brown: Yes. Absolutely. I don’t think in poems usually, so when I’m trying to write a poem, I have to open my mind and loosen my thoughts and really think about a subject from an “outside the box” angle. I need to think not just about content, but about sound and the physical appearance of the words on the page. It’s much more complicated than writing in prose, from that angle. But the precision of it feels very freeing.

MR: Aida: THE MOON WITHIN focuses heavily on issues that often accompany puberty: body image, self-acceptance, sexuality, and sexual identity. What prompted you to explore—and celebrate—these vitally important topics?

Aida Salazar: I was inspired to write THE MOON WITHIN as my eleven-year-old daughter began to ask questions about her changing body. As a Xicana feminist, I wanted to offer her a different way into the understanding of this important transformation than I had been given. I wanted her experience to be grounded in body positive self-knowledge and self-love, in a connection to her ancestry, and the power that is inherent in all of that beauty. I’ve been a moon disciple for decades — marveling, exploring, and ritualizing our connection to her — through astrology, astronomy, spirituality, and the study of pre-colonial Mexican history. We held a ceremony to honor my daughter’s menstruation that was informed by this love of the moon. As a writer, I wanted to share our experience of this magical ritual through story with other children. I was very intentional about sharing ideas of the beauty and power of menstruation Mesoamerican traditions teach us that departed from the often-negative views of our current patriarchal and colonized society. I wanted to reframe the conversation around menstruation by showing what would happen if we, in fact, honored and revered these processes instead.

To follow up on what you said Aida, Judy Blume’s Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret was written almost half a century ago (eek!). Why do you think it’s taken this long for the topic to reappear?

Aida Salazar: This reality is really absurd. How is it that every single person on this planet came from a menstruator and yet, the topic of menstruation is virtually absent in middle grade fictional literature? This is arguably the time when it is most life-altering, when it matters most. It is clear to me that this gaping hole in literature but also in the larger dialectic has to do with the colonial, patriarchal, and puritanical beliefs that are dominant today. These inform how societies, the world over, view menstruation and the feminine body. Girls, women and menstruators of all genders have internalized these predominantly negative views relegating nearly every aspect of our cycles into secrecy and shame.

When I went to search for books to help me present puberty to my own daughter, I found dozens of non-fiction books for adults and girls that were written from a Western European perspective and only a couple from a US indigenous lens. When I looked to fiction, I rediscovered Judy Blume’s novel, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret– a personal favorite of mine when I was a child. There were no books that spoke to it from a Latina perspective and certainly none from a Mexican indigenous perspective in either fiction or nonfiction. So, I set out to write a novel that would fill that gap for her and other Latina girls. I wanted this book to be “the book” that they passed among friends, as I did with Judy Blume’s book in the 80’s, because they saw themselves in it as girls but especially as Latinas. I wanted to invoke the beauty and magic that happens during such a tender time but one that was grounded in ancestral tradition. My intention was to have Celi’s story help redefine the conversation – the dominant narrative that girls bodies and menstruation in particular are dirty, to be feared or loathed – into a conversation that celebrates our bodies, honors our natural cycles and our natural connection to the moon. I hope this is only the beginning of this reframing.

Kathy Ceceri’s Edible Inventions: Cooking Hacks and Yummy Recipes You Can Build, Mix, and Grow (Maker Media, 2016) also has some amazing experiments for kids to do with chemistry. She, however, goes a little more out-of-the box and discusses how kitchen gadgets can be used to make butter makers. She ventures into creating gelatin dots, and even agar noodles (don’t eat those!).

Kathy Ceceri’s Edible Inventions: Cooking Hacks and Yummy Recipes You Can Build, Mix, and Grow (Maker Media, 2016) also has some amazing experiments for kids to do with chemistry. She, however, goes a little more out-of-the box and discusses how kitchen gadgets can be used to make butter makers. She ventures into creating gelatin dots, and even agar noodles (don’t eat those!).

Looking for a way to give your students a little more explanation of chemistry terms, and maybe a little history of the subject? Check out these titles, Explore Solids and Liquids! with 25 great experiments by Kathleen M. Reilly (Nomad Press, 2014) and Explore Atoms and Molecules! with 25 great experiments by Janet Slingerland (Nomad Press, 2017) have awesome experiments, but also contain explanations to describe the different parts of chemistry.

Looking for a way to give your students a little more explanation of chemistry terms, and maybe a little history of the subject? Check out these titles, Explore Solids and Liquids! with 25 great experiments by Kathleen M. Reilly (Nomad Press, 2014) and Explore Atoms and Molecules! with 25 great experiments by Janet Slingerland (Nomad Press, 2017) have awesome experiments, but also contain explanations to describe the different parts of chemistry. If you have older students who are ready to learn more about chemistry, have them read The Disappearing Spoon by Sam Kean (Little, Brown BFYR, 2018). This book gives a lively and interesting history of the scientists who discovered the different elements of the periodic table.

If you have older students who are ready to learn more about chemistry, have them read The Disappearing Spoon by Sam Kean (Little, Brown BFYR, 2018). This book gives a lively and interesting history of the scientists who discovered the different elements of the periodic table.

Edible Inventions: Cooking Hacks and Yummy Recipes You Can Build, Mix, and Grow by Kathy Ceceri — Curious kids will devour the experiments in this book as they work their way through the kitchen lab. Projects include 3-D printing with food, cooking off the grid, chemical cuisine, and more.

Edible Inventions: Cooking Hacks and Yummy Recipes You Can Build, Mix, and Grow by Kathy Ceceri — Curious kids will devour the experiments in this book as they work their way through the kitchen lab. Projects include 3-D printing with food, cooking off the grid, chemical cuisine, and more.

Nancy Castaldo

Nancy Castaldo